Earlier this month, the organizers of a white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville aimed to spark a national dialogue about the perceived oppression of the contemporary heterosexual, white male. But their march seems to have spurred another debate — one about free speech and whether the First Amendment protects hate speech.

The question is certainly being asked and hotly debated at universities across the country. In the wake of the Charlottesville rallies that killed one anti-racism protester and resulted in numerous injuries and violent confrontations, Texas A&M University and, more recently, the University of Florida denied requests for Richard Spencer, a self-identified leader of the “alt-right” movement who has called for ethnic cleansing, to speak on their campuses. But UC Berkeley is preparing for a week in which both conservative pundits Milo Yiannopoulos, who has likened black people to apes and feminists to Nazis, and Ann Coulter, who has argued against women’s voting rights, will both be speaking per the invitation of the school’s conservative newspaper, The Berkeley Patriot.

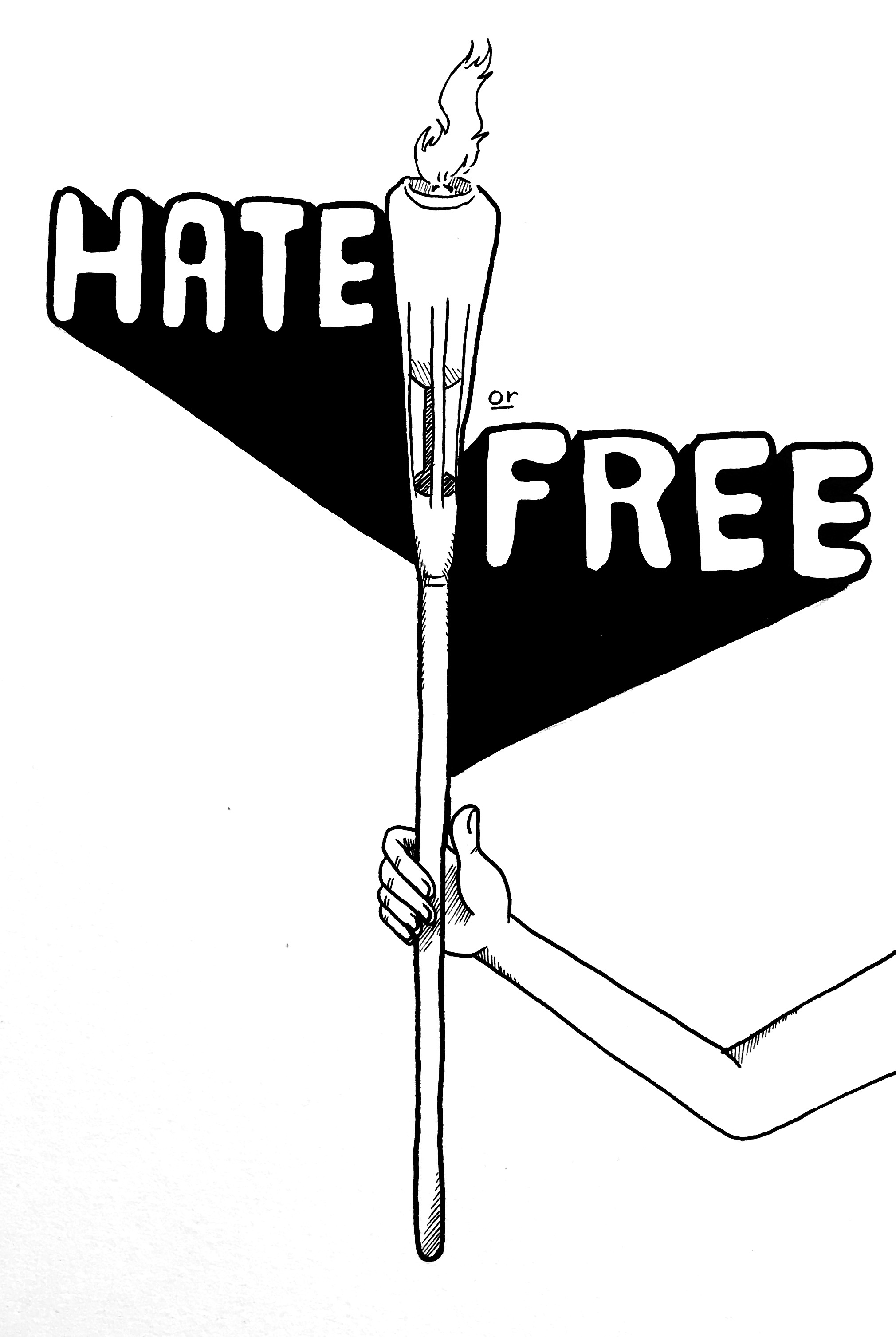

The issue of free speech has been widely discussed on college campuses since the Vietnam War era. Since then, young people have been at the forefront of peaceful protests and political expression. But today’s dialogue on college campuses tends to be laced with misinformation and ignorance about Supreme Court cases and constitutional laws that define free speech. Notably, one thing many self-identified free speech advocates who are quick to take up arms at the first challenge to a provocative speaker seem to forget is that the First Amendment guarantees freedom from censorship — it does not guarantee a platform to spew hate.

The First Amendment guarantees that Yiannopoulos or Coulter could speak their minds in a public place; it does not guarantee them a stage and an audience at a university. In the same way, the federal government and public schools cannot censor nonviolent statements, but simultaneously owe no obligation to stream individuals on Facebook Live or bring them to speak before the White House lawn. Refusal to offer this platform is not a violation of someone’s First Amendment rights. Newspapers have no obligation to publish op-eds or letters to the editor that they are disinclined to for whatever reason, and the federal government cannot censor newspapers.

And in the same vein, Twitter and many other websites, social media platforms and hosting servers are private domains and it is fully up to their discretion how hate speech and harassment are dealt with. The First Amendment delineates the obligations of government institutions; these same obligations are not shared by private companies.

Google had the right to terminate an employee whose speech directly targeted a demographic of employees and established a hostile workplace environment earlier this month. The argument that a private company violated the First Amendment is a moot one, and the argument that individuals can say and do anything in their places of work without consequences is the same argument that justifies — and even encourages — sexual harassment and bullying.

Circling back to college campuses, UC Berkeley has been the epicenter of the campus free speech debate since a violent riot predominantly led by anarchists unaffiliated with the school unfolded when Yiannopoulos last tried to speak earlier this year. But it’s important to note that students who protest speaking appearances by the far-right are not violating anyone’s free speech rights either. If anything, young people who protest provocative speakers are simply putting their own free speech rights to use, and learning important lessons about speaking their minds and fighting for their convictions.

In either case, it’s often not universities but campus organizations that are inviting controversial speakers. And if universities deny the appearances of these speakers, more often than not this is out of safety concerns rather than malicious attempts at censorship. Doing so is certainly not a violation of anyone’s rights.

The free speech debate can seem polarizing on college campuses, where people who have never been the subject of racial hatred and stereotyping, nor of sexual harassment and bullying, argue that individuals should be allowed to say anything without consequences, and people who suffer from this ambivalence toward racism argue the opposite.

Still, there is one bipartisan line of thought, which suggests that speech that is simply advocating contrarian ideals — that women are biologically inferior to men as intellectuals, that African Americans are biologically inferior to white people — but isn’t overtly violent, ought to be respected and even given a platform. This suggests that any comments, as long as they’re short of directly calling for violence, are protected.

However, this should raise the question of how taking away women’s right to vote or be in the workplace, or removing minorities from the country and implementing ethnic cleansing — the concepts demanded by much of the speech of the “alt-right” — could be done without violence or the threat of it. And welcoming these ideas on campus may not celebrate or glorify hatred, but doing so certainly contributes to normalizing it. In the same vein, equating this hate speech to “left-wing extremism” — the alt-right’s term for calls to respect the pronouns of trans people and establish a national health care system — is a ploy to equate a vocal movement for equality to a vocal movement for inequality.

Too often in the campus dialogue around free speech are the most direct stakeholders marginalized. In society today, individuals of marginalized demographics are intimidated and pressured into silence when high-profile speakers come to preach about white supremacy and patriarchy. Their voices are excluded from a media narrative told by majority white reporters, and their experiences are undeniably being overlooked by a U.S. Congress that is 80 percent white, 80 percent male and 92 percent Christian.

The exclusion of minorities and marginalized Americans from our collective national dialogue remains a troubling issue in itself. But all of this is sidelined in a current free speech dialogue dominated by white men who feel victimized by being discouraged from saying the “N-word.”