In addition to well-known painters like Willem de Kooning and Helen Frankenthaler, Christie’s Post-War to Present sale shines a light on under-recognized abstract artists from the 20th century

In his essay Modernist Art, from 1961, the critic Clement Greenberg argues that painting should be a ‘pure’ activity, that its meaning should come from within the confines of the canvas, rejecting emotional expression, illusionism, and ‘any space that recognizable objects can inhabit.’ Modernist, or abstract, painting in the 20th century had to disentangle itself, he said, from other mediums and methods, stripping itself back to its barest essence: paint on a canvas, materiality and texture.

On 29 September, Christie’s Post-War to Present sale will feature the emblematic artists of 20th century abstraction — from painters like Willem de Kooning and Helen Frankenthaler who, as part of the seminal generation that forged a world within the confines of a canvas, have been widely exhibited around the world, to others like Stanley Whitney, Frank Bowling and Lynda Benglis, whose pivotal contributions to the genre have recently come back into the spotlight and are now receiving wider recognition.

Whitney, born in Philadelphia in 1946, moved to New York in 1968 and began honing his abstract visual language. His tendency toward true abstraction and his early experiments in colour blocking would make his work distinct from other more political and theoretical artists in the city, who were concerned more with confronting themes of racial and cultural identity.

The style he employs in Midnight Hour owes to this appreciation of Color Field painters and Minimalism, but was truly developed in the 1990s following time spent in Italy and Egypt. As he said in an interview with Grégoire Lubineau in 2018, ‘When I went to Egypt I realized I could put all the colour together and not lose the air: I realized the space was in the colour. That’s when I started making my mature paintings. 1993, 1994. I went there, and I was like “Got it!” Density was the last piece of the puzzle.’

This density was not just filling up space. It was about appreciating the weight, the airiness of a colour on its own, and seeing how that changed the airflow throughout the piece. ‘How could one create space in the colour on a grid?’ questioned Whitney, when asked about the origin of this style. ‘How could I lay two colours so close to each other and not trap them, but rather allow air for the canvas to breathe?’

He would share with other artists this appreciation for alternate perceptions of colour. Whitney in his ‘mature paintings’, as he calls them, became most concerned with this interaction between density and airflow — ‘space in colour, instead of colour in space.’ Other artists, like Josef Albers when he emigrated from Germany to the United States, used geometric, grid-like compositions in a different way. Rather than studying their mass, he explored how they directly interacted on the canvas.

A student and eventually a teacher at the Bauhaus, Albers was forced to leave Germany after pressure from the Nazi party necessitated the closure of the school in 1933. He found a teaching position in the United States, at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which allowed him the freedom to continue his work and to bring his artistic philosophy to a new group of students.

When he started teaching at Yale in 1950, he had begun working on the series of paintings that would consume the next 26 years of his life: Homage to the Square. Over hundreds of iterations in which the artist nested three or four squares, he explored colour and its possibilities for conveying subjective experience within a tight geometric constraint. The three works offered in this sale — Budding, Spring out, and Home-Coming — were made between 1958 and 1962, well into his study of the form.

He said of the series in 1965: ‘They all are of different palettes, and, therefore, so to speak, of different climates. Choice of the colours used, as well as their order, is aimed at an interaction — influencing and changing each other forth and back.’

In his geometric abstraction, Albers found the freedom to explore the emotional lives of colours through a series of restraints. By dividing his canvas into a series of squares, he could best understand and expose their relationships to each other. Later artists would approach this differently, taking form and texture as a requisite avenue of exploration in tandem with colour.

Working mainly in sculpture, Lynda Benglis used beeswax before moving to latex, polyurethane, gold leaf and aluminium in the 1970s. Her dramatic entrance into the New York scene was marked by the physical nature of her medium, and how she used it to confront ideas of representation in the art world.

Her works using phosphorescent paint, chicken wire and Pollock-esque paint effects were highly suggestive and open, in stark contrast to the male-dominated Minimalism of the era. For example, Untitled from 1970, a multi-coloured polyurethane foam pour that is at once candy-coloured and excremental. Its composition directly reflects Benglis’ act of creating: lugging around half-gallon buckets of latex, she would sacrifice a sense of control, letting the medium act of its own volition rather than trying to tame it.

Benglis’ work was neglected for a long time, with many finding it too charged or dismissing it for its sensual overtones. Since 2009, however, a renaissance of her work has been in process, with museums around the world — most recently the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, Texas, in 2022 — seeking out her work for retrospective exhibitions.

Engaging directly with the confines of the canvas itself, the American painter Sam Gilliam began working on a series of ‘drapes’ in the 1970s. These stretcher-less painted canvasses were suspended from the walls or ceilings of galleries, giving a more tactile presence to the usually two-dimensional medium.

Made by an African-American artist working out of the nation’s capital at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Gilliam’s experimentations were more than an aesthetic proposition or critique: his ‘drapes’ were a way of redefining the role of art in a society undergoing dramatic change.

Gilliam was inspired by jazz musicians like John Coltrane. He told The Art Newspaper in 2018, ‘the composition is always present but one must let things go, be open to improvisation, spontaneity, what’s happening in a space while one works.’ Idylls I, an early drape painting from 1970, shows his interest in the Color Field painters as well as the Lyrical Abstraction of the late 1960s.

At the same time as Gilliam was continuing to develop his practice, the Guyanese-British painter Frank Bowling was gaining acclaim in New York. He had arrived in the city in the late ‘60s after completing his education at the Royal College of Art in London, where he received the silver medal at graduation — gold went to his classmate, David Hockney.

In his solo show at the Whitney in 1971, as well as his 1972 appearance at the Whitney Biennial, critics commented on the differences between him and other British painters in the States, who were predominantly making pop art. In contrast, Bowling wielded the dual approach of Bacon-esque figurative painting — which he deeply admired — and abstraction, punctuated by personal emotion. In New York, he came into contact with Clement Greenberg, who became a close friend and encouraged him to further his study of abstract art.

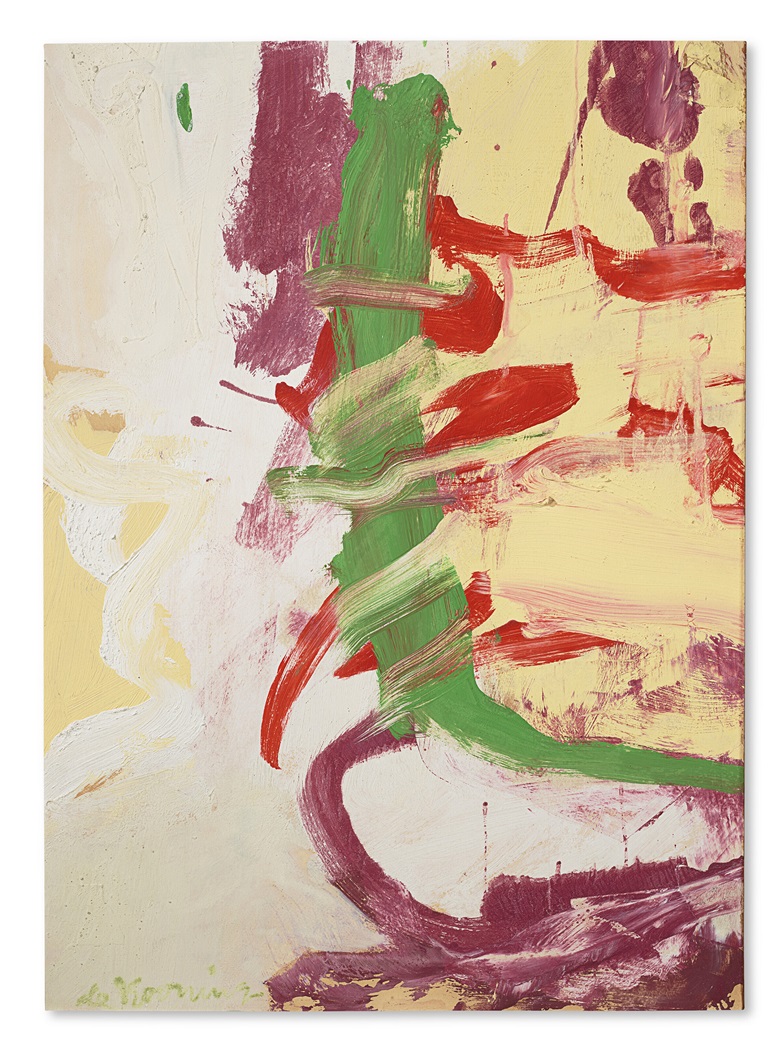

Barnica Flats VII, named for the Guyanese coastal town where he was born, is one of Bowling’s later poured paintings. Unlike some of the poured paintings which he began making around 1973, this one was not made by just pouring layers of pre-mixed, contrasting paint. Instead he is working more on the surface, using paints of similar tints and applying them with a variety of techniques like pouring, dripping and spattering. In line with Greenberg’s theory of abstraction, Bowling emphasizes the visual aspects of the artwork over its narrative content, but he also demonstrates absolute control over the apparent randomness to which his process lends itself—a process which he had been studying throughout the 1970s. This painting shows his refined process through an ability to balance deliberate compositional approaches with accidental gestures caused by movement of the paint.

Bowling was directly inspired by Greenberg, but the historical progression of abstraction through the 20th century would only occasionally align with this theory of art. More often, artists truly seeking to learn about their own process went further than simply exploring the interior and exterior of the canvas. The most radical approaches came from artists who blurred or even dissolved the borders between mediums, like Lynda Benglis and Sam Gilliam.

Sign up today

Christie’s Online Magazine delivers our best features, videos, and auction news to your inbox every week

Subscribe

When we think of abstraction, often our focus brings us to the established names of the genre. Artists like de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, experts in colour and form, inspired generations of artists after them. They served as inspirations to their peers, those who partook in the Ninth Street Exhibitions, and who were key members of the Greenwich Village scene in the mid-20th century. Inseparable from the history of American-based art, and seminal in the development of modernist abstraction, other artists — like Bowling, Gilliam and Benglis — still have their own stories to tell.

RankTribe™ Black Business Directory News – Arts & Entertainment